Why is Argentina’s economy so bad? Does Javier Milei have the answers?

Media Landscape

See who else is reporting on this story and which side of the political spectrum they lean. To read other sources, click on the plus signs below.

Learn more about this dataLeft 24%

Center 35%

Right 41%

Simone Del Rosario: People in Argentina are ready to take a chainsaw to their economy. You may have heard a little about who they just elected president. Javier Milei is a shaggy-haired, rockstar-esque, eccentric economist who fashions himself an anarcho-capitalist.

People call him Argentina’s Trump, but President Trump never destroyed the U.S. Central Bank. Milei has said he wants to blow up the country’s central bank, but that’s not all. He’s vowed to shutter entire government agencies and trash the Argentine peso, with hopes of making the U.S. dollar the national currency.

Javier Milei: This is not a task for the lukewarm, not a task for the cowardly, and much less for the corrupt.

Simone Del Rosario: And after years of calling those in Congress corrupt, Milei doesn’t have a ton of friends there, which’ll make it hard to pass his more extreme policies.

Give ‘Em Hell, Harry: You want a friend in this life, get a dog.

Simone Del Rosario: Advice Milei takes to heart. He cloned his beloved former dog, Conan, producing five genetic matches. The English mastiffs, he says, are his children and his political advisers.

Argentina man: I personally didn’t vote for him because I felt it was like a leap into the void. God willing he surprises us.

Argentina man: Between the two options, I think the best one was him. Milei comes from the outside, so he convinced me more.

Javier Milei: With me, the decline ends and we regain power. Long live freedom, damn it.

Simone Del Rosario: So why did Argentina’s voters overwhelmingly elect a man who’s promising to blow up the economy? Probably because it’s been a disaster for decades.

Laurence Kotlikoff: Did Argentina ever have a single crisis that put it down, you know, produce a great depression or lead everybody to leave the country? No, it’s been a series of many crises through the years.

Simone Del Rosario: A century ago, Argentina was one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Rich in natural resources. Fertile land. On parity with the United States.

Laurence Kotlikoff: Argentina, in 1920, had 85% of our per capita GDP. They were almost as rich as we are. Today, they have 14%. It’s all due to running these policies over a century. So this is a slow train wreck.

Simone Del Rosario: A train wreck many economists say started under Juan Domingo Perón. A three-time populist president first elected in 1946 who ruled on socialism with a side of fascism.

Perón drastically expanded social welfare programs, nationalized industries, monopolized foreign trade, and pushed wages higher.

As a result, growth in Argentina paled in comparison with countries it once competed with. The peso lost value. And inflation took hold.

Though Perón was eventually overthrown in a military coup, Peronism persisted. Perón was even brought back from exile for a third term. And Peronist candidates have largely dominated the political landscape.

Argentina woman: I am a Peronist, and whoever is the Peronist candidate, I will always vote for Peronism.

Simone Del Rosario: Milei’s opponent, Sergio Massa, was the Peronist candidate in the presidential race. And voters this time resoundingly rejected those ideals.

Try shopping within your budget in Argentina when prices literally change by the day.

Argentina woman: Whatever you buy one week, the next it will be priced differently.

Simone Del Rosario: Think inflation in the U.S. is bad? While the U.S. peaked at around 9% this cycle, people in Argentina are looking at 143% in annual inflation, with the central bank predicting 185% by the end of the year. That’s not a fat finger error. Argentina is living through triple-digit inflation, among the highest in the world.

Despite generous government subsidies, 40% of the population lives in poverty. Meanwhile, the value of Argentina’s currency continues to plunge.

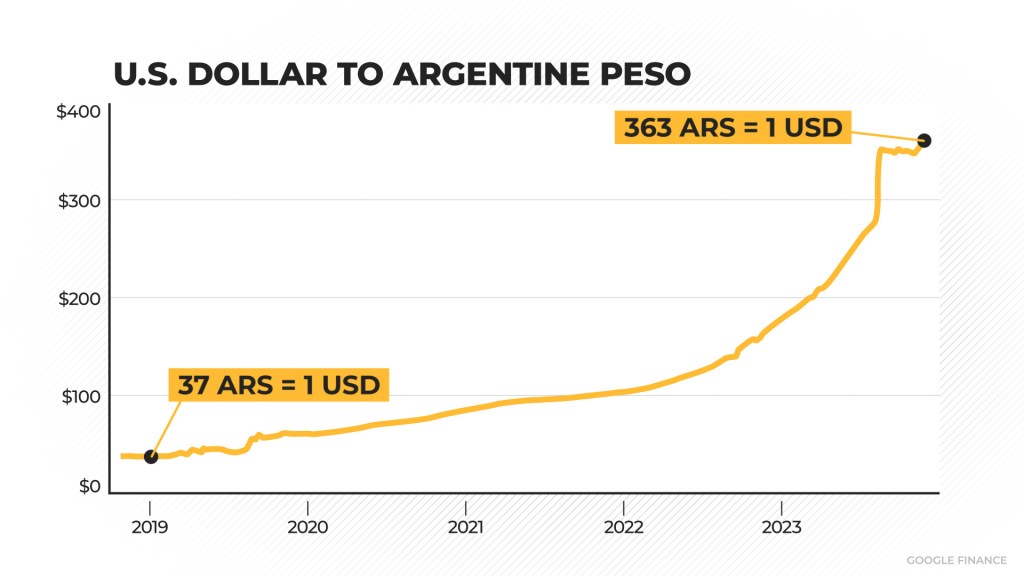

Five years ago, 37 Argentine pesos could buy one U.S. dollar. Today, it takes more than 360 pesos to make the same exchange.

With no faith in their own currency, people in Argentina literally stash U.S. dollars under the mattress for safekeeping, knowing any pesos they hold will rapidly lose value.

Many turn to the black market to buy elusive dollars, which in October went for nearly three times the listed exchange rate.

Here’s a country that boasts the second-largest economy in South America, behind Brazil. The World Bank sees it as a nation with significant opportunities. But they’ve been out of balance for decades.

Argentina has defaulted on its debt nine times. The last three have happened since the year 2000. Who would lend money to a nation that can’t pay its debts? Argentina is by far the biggest debtor to the International Monetary Fund, with about $44 billion in outstanding debt.

Stephanie Kelton: Countries like Argentina and Venezuela and a whole host of other countries, for in many cases very understandable reasons, take on debt that is denominated in currencies that are not their own. So they get loaded up with debt, they get IMF loans and the rest of it. Some countries just don’t have much of a choice. They don’t have domestic energy resources, they don’t have access to food and medicine and technologies, they’ve got to import these things. And to get those real resources they often have to acquire so-called hard currencies, they need the U.S. dollar or the euro or the pound. So they get indebted in currencies that they can’t issue. And then it’s no surprise when, you know, a country like Argentina that can do very well for a period of time because it’s a big exporter of things like soybeans, if soybean prices are very high and rising, well all of a sudden Argentina is doing very well. And then when commodity markets take a tumble and prices come crashing down, all of a sudden, you’re not earning the foreign exchange that you need to service debt that you’ve taken out in other people’s currencies. So you can get a debt crisis in a country like that.

Simone Del Rosario: And this year, with the drought, Argentina’s economy is expected to contract by 2.5%.

Laurence Kotlikoff: We’re kind of Argentina in the making.

Simone Del Rosario: Argentina serves as a cautionary tale for other economies. A scary story told to say, don’t follow this path or you too might end up here. As total U.S. debt flirts with $34 trillion, American economists are quick to compare the fundamentals.

Kevin Hassett: That we’ve increased it so much that for example, our debt relative to our national income, to our GDP, is about 40% higher than it is in Argentina, a country that everybody knows is potentially in trouble.

Simone Del Rosario: Will U.S. spending spiral the country to Argentina’s depths? Economist Stephanie Kelton says there’s one clear difference between an Argentina and the U.S., or even Japan, which holds twice as much debt as the U.S. when compared to the size of their economies.

Stephanie Kelton: Japan, the U.S., the UK, Australia, Canada, these governments are currency issuers, right. They’re not going to run out of their own currency. They never have to borrow it from anyone in order to be able to spend.

Simone Del Rosario: One of Milei’s chief pledges, dollarizing Argentina’s economy, would mean letting another country drive its currency destiny. But doing so would eliminate a lifeline that has for decades fueled Argentina’s inflation: printing pesos to cover the country’s overspending.

The U.S. has no control over whether a country adopts the dollar. And experts doubt Argentina could come up with enough dollars to transition. But the U.S. Treasury has warned countries in the past that dollarizing is not a substitute for sound fiscal policy.