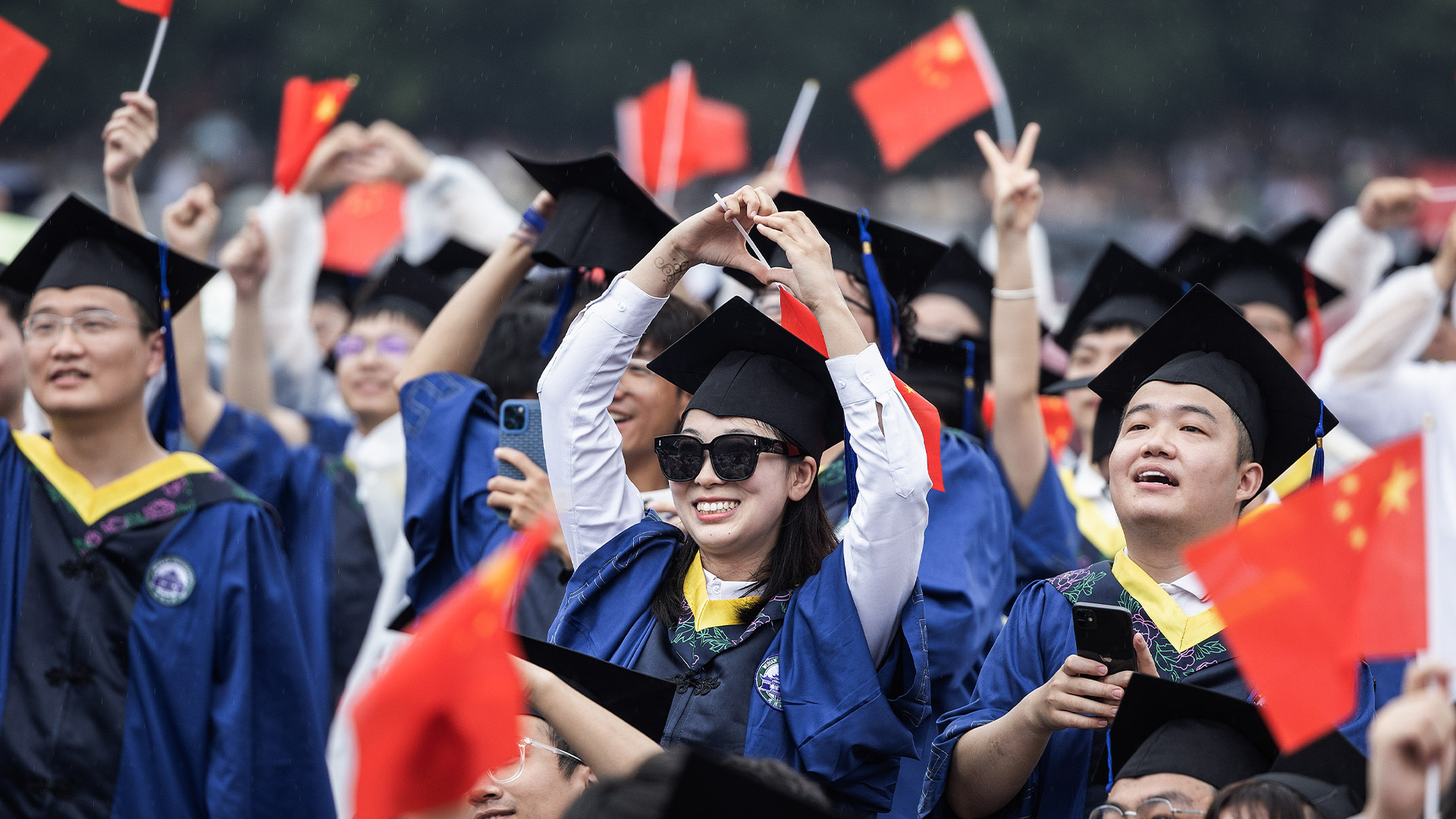

Simone Del Rosario: They were told with hard work and a good education, they’d get the career of their dreams.

But for many young adults in China, that is simply not the case.

For a couple of years now we’ve been hearing about the “lying flat” or “let it rot” youth in China, a characterization that the kids are lazy and don’t want to work.

But there’s way more to the story in the world’s second-largest economy.

Recent graduates are dishing out, in some cases, more money than they can hope to make in a job, for interview coaches and job agents.

A Bloomberg article said some students are paying $50,000 to try to land a finance job.

And still it’s not enough.

China’s youth unemployment surged to 17.1% in July, up from 13.2% a month earlier. And this new measure of youth unemployment excludes current students.

Remember, last year, China’s jobless rate for 16- to 24-year-olds reached 21.3%, so high the government stopped reporting the data after that. The government agreed on a new method to exclude students which is fine except even without them the rate is above 17%.

Now these young graduates have a new name, “rotten-tail kids.” It comes from the millions of unfinished homes that litter the country known as “rotten-tail buildings,” real estate dreams that never came to fruition.

China scholar and professor of global leadership at Arizona State University Doug Guthrie joins me now.

Doug, what would you say is the primary issue with young graduates landing jobs in China?

Doug Guthrie: I always like to put these things in context as you know, and so China is going through a dramatic transformation, and has been going through that transformation for the last 40 years, and in particular the last decade has been a new era of transformation in terms of where the economy is going and how to move from just a highly industrialized economy to a tier one economy, and an economy that is doing well in things like high end service sector economy, and so they’re still building. But the context that I like to put out here, just to remind people, you know, the one child policy has been in play for about 40 years, and it’s really been kicked in strongly over this time period when it was put into play, China had a serious population problem, and it seemed like a necessary approach to really dealing with the number of people that lived in abject poverty, and really trying to figure out how to move forward with economic growth. When it looked like China was going to go below replacement rate, about a decade ago, they changed the one child policy back,to saying you could have multiple children. This was 2016 and I think what the Chinese leaders didn’t realize, and as a sociologist, I was quite fascinated by this, because you can have laws and policies, but then eventually those laws and policies become culturally embedded. And so, you know, when you open the door and said, Now you can have multiple children because we need more replacement of the population, people thought, well, actually, you know, we’re our ideal notion of what a family is is three people and it’s a child and two parents and four grandparents and and so it just people didn’t start having kids immediately. And so there is an entire generation of children who have grown up under the one child policy. And some people who are experts on studying Chinese society would argue that these kids have developed a different sort of sense of self, and they’re very demanding and have high expectations in what kinds of jobs they want. And so when you graduate from from college and you need to go get a job, and the numbers always spike in July, because you have a group of graduates that come into the labor market in June. And it used to probably be the case that people were urgently thinking about jobs, jobs, jobs. And now those children have two parents and four grandparents who are very much focused on their well being. And maybe they’ve become a little bit more willing to wait and think, Well, if I don’t get the perfect high end service sector economy job that I want. I’ll just continue to live at home. And so people are a little more selective, I think, with how they’re thinking about so I think the one child policy is an issue here that is not to diminish the issue that you know this. This is an economy still in transition, and so I think there’s a lot going on. I’m just less concerned about the numbers right now, because I want to see what happens. You know, we’ve seen a spike from 13% to 17% but I want to see what this looks like two or three months from now.

Simone Del Rosario: But even before these numbers came out, these young graduates were having issues finding jobs that suited their qualifications and the degrees that they had. Are the jobs there. For, you know, students or postgraduates who are qualified for certain tasks, or was this promise to get an education and you’ll have a good paying job at the end of it was, was that not real? Was there no, you know, gold at the end of the rainbow?

Doug Guthrie: Well, here again, I would like to you know, if you divide the labor force up into multiple categories, okay? So you have, you know, the the migrant labor force, which is the sort of menial jobs within factories and in the agricultural economy. But let’s leave the agricultural economy aside for a second. But so you have this one sector of the labor force that kids who go to college are not going to participate in, right? Like these are line workers in factories, right? And then you have a second layer of the labor force, which is the vocational technical education. And the Chinese government, in my opinion, has been very smart at investing in vocational technical education, because that level of the labor force is really necessary for thinking about, okay, you have menial workers, and they are the people that are just putting things together on lines. And then you have people who actually know how to build complex factory systems and manage them. They are not high end managers, but they are the vocational technical labor force. And China has invested heavily on still, college kids probably don’t want those jobs, right? Like those they want to, you know, they’ve sort of learned liberal arts, education or engineering, and they want something that’s in the high end service sector economy. And this is where, you know, you get into general management, managerial labor force and high end service sector economy. And you know, there’s a lot of powerful companies, both in high end service sector economy economy, but also in the management of major manufacturing firms. Most of them have business school degrees, and most of them have really kind of gone beyond their next level of education. And so I do think that there’s just a gap here for this college educated 18 to 24 year old or 16 I guess they’re not doing the school students anymore, and so it’s just the 18 to 24 year olds that are in that category. And so it may be the case that there’s just not enough jobs for what their expectations are in jobs, and they may have to just dial back those expectations a little bit. And again, to this point there is, there’s big differences across cities and provinces, but where we’re really seeing the joblessness is in the high end, tier one and tier two cities. Yeah.

Simone Del Rosario: Okay, so what is the typical graduate doing when they can’t find a job? You know? What makes them this rotten tail kid, as they’re calling it?

Doug Guthrie: So here again, this is where I think things get and, you know, I don’t love the rotten tail kid naming of it, because they’re, you know, the these are kids, again, that are have been catered to through their whole lives, they’re the only child in their family. And their families have said, we’re going to put you, put all of our resources into you getting through high school and then going to college and really having just a great life ahead of you. And so, you know, they’re a little entitled, and so and their families, most of them, have homes and apartments that they can just move back into, and there’s only one child to be worried about, and they’re the focus of the family. And so that entitlement is leading to the set of decisions, well, okay, I’ll wait. I’ll wait for the perfect job. And so I think that is causing a lag in the labor market, rather than people feeling urgent, like, oh my goodness, I need to get out and get a job because I’m out of college, it’s just a different cultural mindset in China about that. So they’re waiting. And, you know, I mean, it’s, you know, the waiting for employment is a category in China, and so, you know, it’s sort of an interesting you have, you have students, and then you have employed people, and then you have unemployed people, but you also have this separate category that’s called diale, which means waiting for employment. And so people just think, Okay, I’m just waiting. And then when you get into this, the more striking thing that about what you’re reporting on is that families are investing so much in these headhunting and coaching firms at this this age. It’s, it’s quite remarkable. I mean, again, it’s, it’s a little bit sort of touching in terms of telling you what the one child families are like, at least at the higher end of the socioeconomic spheres. These families are investing in their children, but it might be that they end up being a little bit spoiled in terms of what they’re waiting for, and not willing to compromise.

Simone Del Rosario: President Xi says that this youth unemployment problem is a priority for him, but it doesn’t seem to really be getting any better. Do you? You know, know what that policy is, what they’re trying to do to improve this situation?

Doug Guthrie: Well, so here again, and you and I have talked before, so I’ve given me, if I’m repeating my the hobby horse I’d like to get on. But you know, the China works in a very interesting way, in terms of President Xi will say, this is a priority for me. So youth unemployment is a priority. And that sort of comes out of the five year plan, and it comes out of the yearly state council meetings. But the way the economy is set up is local officials and my group. We like to call them local governments as industrial firms, and so the heads of provinces, the governors of provinces, but more importantly, the mayors of cities. It’s their job to really think about creative ways to do things like build industrial clusters or create different economic circumstances. And you know, this is really the engine behind what has made China’s economic growth so strong is because you have these very entrepreneurial leaders, and Xi Jinping was one of them. I mean, he was, you know, part of the reason he became president was because he led Zhejiang province, and Zhejiang Province was just a masterpiece of economic development and innovation. And so these players at these local levels are very aggressive, and they’ve become very, very good at doing things like building high tech industrial clusters, you know, like Jiangsu Province leads the world in both photovoltaic arrays and technology around that, but also electric vehicle batteries and and so they’re very good at that. But my sense is they and this comes from, directly from some interviews I’ve done in recent visits to China. You know, when Xi Jinping says, Oh, the big problem now is youth unemployment, they need to spend a little time thinking about, like, how are we going to solve that problem? So for Xi Jinping, he said it’s a priority, and he has it, but they don’t have a national policy on this. What they’re waiting for is the local officials to do their job and be innovative around it. And people are still trying to catch up.

Simone Del Rosario: All right, Doug Guthrie, China scholar and professor of global leadership at Arizona State University, it’s always good to talk to you about what’s going on in China.

Doug Guthrie: Thank you so much. Wonderful to talk to you. Thanks for having me.